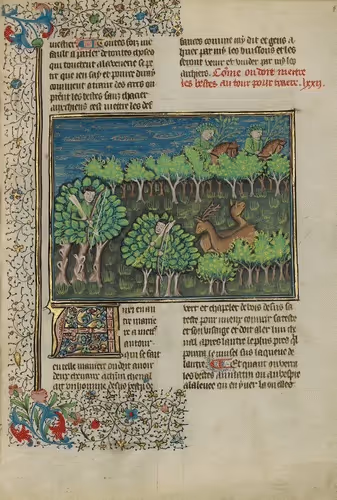

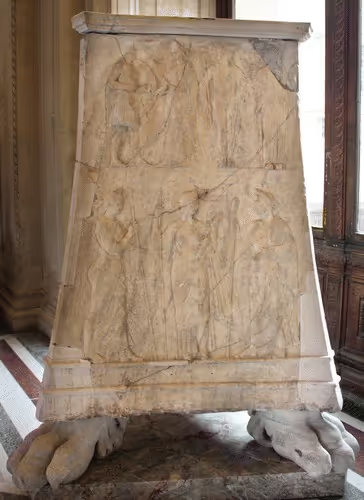

Camouflage and mimicry are not the domain of animals alone. Humans also engage in these image-making practices, in hunting, war, fashion, social behavior, and the arts. Consider, for instance, an Anglo-Saxon ornament from Sutton Hoo in which animal figures are hidden in a trellis of metal straps (fig. 1). Hunters use camouflage, covering themselves in foliage, as in this fifteenth-century manuscript illumination (fig. 2), or disguising themselves as white wolves in George Catlin’s North American Indian Portfolio (fig. 3). In the arts, camouflage sometimes takes the shape of zoomorphism: this base of a Roman altar from the second century CE looks like a lion partly disguised as a trapezoidal piece of sculpture (fig. 4). Camouflage is also present in many other varieties of disguising, hiding, and covering to be found in the decorative arts and fashion. See, for instance, the practice of hiding brickwork behind oak paneling, which in this example is made to look like linen folds (fig. 5). Among humans, camouflage also occurs in social behavior, as when people disguise their social status, desires, or motives behind appearances they judge to be more acceptable or effective. The novels of writers such as Thomas Mann, Marcel Proust, and Honoré de Balzac are full of social camouflage.

These examples of what might provisionally be called the shared domain of animal and human camouflage and mimicry raise many questions about the psychological, evolutionary, and behavioral relations between animals and humans. For art historians, visual similarities between animal and human camouflage are baffling, as are most cases of image-making that transcend the human/animal divide. One of the few exceptions is the painting animal, particularly in depictions of monkeys as painters.1vVisual similarities between human artifacts and animal camouflage, such as those between the Roman altar (see fig. 4) and the hermit crab shown in figure 6, could be considered instances of pseudomorphism, which Erwin Panofsky defined as “the emergence of a form A, morphologically analogous to, or even identical with, a form B, yet entirely unrelated to it from a genetic point of view.” Invoking pseudomorphism is the art historian’s way of noting enigmatic formal similarities while dismissing them as fortuitous because there is no evidence of a historical connection between the forms nor is there any convincing conceptual link.2

On the other hand, giving an exclusively evolutionary account of the relation between animal and human camouflage is also problematic. Biological evolution is much slower than cultural developments; animal camouflage is genetically determined and shaped by instinct and successful adaptation, whereas human camouflage is taught, conscious, and often intentional. Therefore, there is no direct, causal relation between the two. Also, the fact that camouflage was first theorized in the context of the evolution theory developed by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace does not imply that evolution offers a complete explanation of human camouflage. Ultimately, the fact that humans engage in camouflage and mimicry does not require an evolutionary explanation. Humans are animals and therefore share survival and other skills with animals, but seeking an evolutionary antecedent or cause for human varieties of camouflage might be described as a misguided exercise in skeuomorphism. In design studies this term refers to the use of existing forms for new inventions, in the way that the first printed books were designed to look like manuscripts, or a Mac hard disk to resemble an eighteenth-century Japanese lacquer writing box. When applied to camouflage, it would suggest that human camouflage is a spurious throwback to older, animal behavior.

To clarify the relation between animal and human camouflage, I want to reconstruct some main points of the archaeology or prehistory of thinking about camouflage and mimicry as shared animal and human features and present aspects of the cultural contexts in which such thinking took place: the hunt, dissimulation at court, and the arts considered as masquerade. This prehistory, largely obscured by the focus in current scholarship on the evolutionary and military aspects of camouflage, will significantly extend the range of examples and ideas that existed about these same topics prior to their present codifications.3 It will also show that military and evolutionary conceptions of camouflage have obscured its much wider role, which goes beyond protective adaptation and should be considered as a cultural technique in humans. Three stages will be examined in this prehistory—stages that are also varieties of cultural contexts. In the first, camouflage behavior is discussed as a common feature shared by animals and humans in the hunt, where both can be hunter as well as prey; in the second, camouflage among humans is discussed in terms of simulation and conceived, or figured, in terms of animal behavior; and in the third, camouflage is seen as the manifestation of emerging human material culture.

This last stage provides a direct link to considering human camouflage as a cultural technique. This I define, following Thomas Macho, as a symbolic technique that cannot be produced without a medium and at the same time cannot be reduced to it; that allows for self-referentiality or thematization; and that is older than its conceptualization. The cultural techniques of writing, singing, and weaving, for instance, existed before they were codified in writing and, unlike ploughing or fishing, can be thematized: one can sing about singing or weave a tapestry that depicts weaving, but one cannot represent fishing in an act of fishing. Another important aspect signaled by Macho is that cultural techniques are often techniques of the self: they serve to present or construct a certain identity.4 To Macho’s definition I would add that cultural techniques often emerge on the cusp of the transition from instinctual, innate behavior to cultural and learned activities and the production of artifacts. Thinking about human camouflage in these terms will help to address the problems raised by evolutionary explanations of its development. Evolution theory has made the study of this subject particularly complex because of the clash between the longue durée of evolutionary development in nature and the short time span of cultural developments and because of the lack of fit between the low resolution of evolutionary analysis— considering developments of species over long periods—and the close scrutiny, in culture studies, of individual cases over short periods. 5

1. Camouflage and mimicry: some preliminary definitions

The term camouflage is a recent one, first attested in 1887 in French and subsequently in English.6 It is derived from the noun camouflet, first documented in 1611 in the sense of smoke blown into somebody’s eyes.7Whereas biologists generally use the term camouflage to refer to the protective characteristics an animal takes on to blend with its inanimate surroundings, mimicry refers to an animal’s adoption of the behavior and appearance of another animal.8 According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word mimicry, defined as “the art of depicting character by mimetic gestures,” was first attested in 1637 and derives from the Greek ethologia, the understanding of character as displayed in behavior. The term was first used in entomology in 1815 in William Kirby and William Spence’s An Introduction to Entomology. 9 In a discussion of what would now be called camouflage, the authors cite the case of Leptocerus atratus, a kind of mayfly that resembled its habitat so closely that they were often unable to distinguish the insect from the plant it frequented. “The birds,” they wrote, “probably often make the same mistake and pass it by.” 10 At present, mimicry is generally understood to encompass crypsis, the use of strategies to prevent detection, and masquerade, which aims at avoiding recognition by the predator. 11

Camouflage became a central issue in the life sciences as a result of the discoveries by Bates, Wallace, and Darwin, in the 1850s, of adaptive behavior as a means of survival.12 In biology, camouflage quickly became a central testing ground for evolution theory because it enabled investigators to observe in nature how the adaptation of species to their environment evolved and how exactly the fittest survived. Henry Walter Bates’s study of mimicry among butterflies, first published in 1862, was one of the first independent fieldwork confirmations of Darwin’s theories.13 Bates showed, for instance, that the Leptalis butterfly, of the Pieridae family, mimics another genus, Ithomia, from the Heliconidae family. Predator birds find the Ithomia revolting to eat, whereas the Leptalis are quite tasty to them. Connecting mimicry to survival by adaptation, Bates showed that the survival of the Leptalis butterflies is based on their quite large numbers; since there is heavy selection and constant evolution of new species, the species that looks more like the Ithomia is more likely to survive.14

Wallace spent much of his life studying camouflage and mimicry behavior among insects in Amazonia, coming very close to being the discoverer of evolution theory. In “Mimicry and Other Protective Resemblances among Animals,” a long essay published in 1867 in which he reviewed various studies of camouflage and mimicry, Wallace set out the state-of-the-art view of camouflage, its role in the adaptation and survival of species, and the problems still unsolved. He cites some wonderful examples, such as the Kallima butterfly of India and Malaysia, whose protective resemblance to its environment is so sophisticated that its wings do not just resemble the leaves, bark, and shrubs of its habitat but also display “powdery black dots” that resemble the fungi on the leaves, thus representing, as Wallace puts it, “leaves in every state of decay” (fig. 7). 15

Such protective resemblance consists not only of a repertory of forms, shapes, sizes, textures, and colors of skin surfaces but also of behaviors and habits. Together these traits produce disguises that are almost perfect, given the large number of insects that possess them. Wallace also notes that such resemblances do not involve conscious, intentional imitation, but rather a patterning and shaping of external appearance that occur in particular among animals that multiply rapidly, with incessant slight variations resulting in successful adaptation and hence survival. The disputed role of intentionality in such resemblances would become a recurring issue among evolutionary biologists, leading to intense debate in Cambridge in the 1930s and ’40s. As Hugh Cott, one of the pioneering students of animal mimicry and particularly of adaptive coloring and patterning in birds, wrote: “An analogy must not be carried too far. The present one stops short at the point where we realize that while man-made contrivances have been invented, natural adaptations have evolved…. Nevertheless both are intimately related to the pressing needs for survival in this transitory life.”16

At the same time, Wallace introduced a gradual shift of focus from camouflage as a feature of the external appearance of animals to camouflage as a variety of behavior: animals often do not look like their habitat but, while remaining quite conspicuous, start to behave like other animals that are less attractive to their predators: “They appear like actors or masqueraders dressed up and painted for amusement, or like swindlers endeavouring to pass themselves off for well-known or respectable members of society.”17

Wallace makes another major point here, asserting that there is no radical division between animal and human capacities for creating camouflage and being fooled by it: “For it is evident that if colours which please us also attract them [animals], and if the various disguises which have been enumerated are equally deceptive to them as to ourselves, then both their powers of vision and their faculties of perception and emotion must be essentially of the same nature as our own—a fact of high philosophical importance in the study of our own nature and our own relation to the lower animals.”18

Camouflage posed two major problems from the moment it became a core part of evolution theory. The first was how to account for the enormous variety of protective adaptation on show in nature. This was a problem because, as the biologist Richard Swann Lull wrote in 1917: “We cannot conceive of selection taking an adaptation past the point of efficacy.”19The second problem was to explain how creatures produce offspring that are like themselves but different in subtle visual ways. This would be solved only in the 1960s and ’70s, when evolutionary biology and genomics met and a genetic account of the development and persistence of camouflage over successive generations of an animal species could be developed and tested.20

Accounts of camouflage and mimicry that concentrated exclusively on evolutionary function—on the adaptation of traits solely for purposes of survival—were also criticized by two men who were both artists and biologists: Roger Caillois and Vladimir Nabokov. As is well known, Nabokov came from a family of scientists and spent much of his life, when not writing, pursuing and studying butterflies. He became the curator of lepidoptera at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, identified new species, and published major articles on their classification. He was also fascinated by camouflage and mimicry, lectured on the topic, and worked on a manuscript about it, which is now lost.21 Fortunately, mimicry figures large in Nabokov’s fiction, where he scattered tantalizing observations about the similarities between butterflies and plants, between animals and art, calling them “those rhymes of nature.”22 In The Gift (1933–38) he fires off a series of mimetic disguises that far elude evolutionary explanation:

[An] incredible artistic wit of mimetic disguise, which was not explainable by the struggle for existence (the rough haste of evolution’s unskilled forces), was too refined for the mere deceiving of accidental predators, feathered, scaled and otherwise (not very fastidious, but then not too fond of butterflies), and seemed to have been invented by some waggish artist precisely for the intelligent eyes of man…; [he spoke about] these magic masks of mimicry; about the enormous moth which in a state of repose assumes the image of a snake looking at you … and about the curious harem of that famous African swallow-tail, whose variously disguised females copy in color, shape and even flight half a dozen different species … which are also the models of numerous other mimics.23

These observations all point to the inescapable but inexplicable similarities between animal and human mimicry in behavior and art. Nabokov took a rather transcendental, Kant-inspired position on these similarities: camouflage exists only in the eye of the beholder, and judgments about camouflage are therefore closer to aesthetic judgments than to scientific theories about matters of fact or cause and effect. Also, he argued against Darwinist gradualist accounts of camouflage. For Nabokov, the infinite richness of camouflage could not be explained by the endless hit-or-miss and tinkering of survival by adaptation. Instead, he turned to theorists of morphogenesis such as the French philosopher Henri Bergson, the Russian Lev Berg, and Scottish biologist D’Arcy Thompson, author of On Growth and Form (1917), all of whom argued, in various ways, that the actual life of an organism may affect its development and phenotype, thus influencing its chance of being selected and thus surviving.24

This view raises fascinating issues about the epistemological status of judgments about camouflage and its evolution that cannot be pursued here, but I want to stress how clearly and compellingly Nabokov signals the similarities between natural and artistic camouflage and mimicry. At the same time he emphasized the problems of producing an economical theoretical and historical account of the actual evolution of camouflage and mimicry through the long periods of species development.

The poet and historian of biology Roger Caillois (1913–1978) provides a very different perspective. In his youth he was part of André Breton’s Surrealist circle. Caillois’s early, prewar writings on praying mantises and other picturesque insects can perhaps best be described as essays in the cultural history of biology. They question how certain animals, such as the praying mantis or the jellyfish (suggestively called méduse in French), can over the centuries acquire such rich incrustations of myth, beliefs, and psychoanalytic theories.25 In his prewar work Caillois connected camouflage in animals and humans to all kinds of psychopathology and even to the human desire to disappear into petrification and nothingness. His 1963 book on animal mimetism, Le mimétisme animal, far less known, is a much more sober affair. It is concerned with developing an understanding of camouflage that goes beyond evolutionary monocausalism. Caillois presents only one argument, but one that is difficult to ignore. Very often, camouflage does not work effectively in nature because, for instance, a predatory animal can still smell its prey despite the latter’s careful disguise as a piece of rock or a staring owl (fig. 8). The formal repertoire, and behavior, of camouflage is far too lavish, elaborate, varied, and luxuriant to serve the sole purpose of protective adaptation. As Caillois put it: “Camouflage is often useless…. There is a luxury of precaution, and an excess of simulacrum.”26

Caillois subsumes camouflage and mimicry under the broad category of animal mimetism: the ability of animals to display appearances that imitate traits of other animals or their environment, often without conscious intention or comprehension. The formal similarities between animal mimetism and human image-making raise the question of whether there are any connections between the two. Caillois argues that there is a clear connection: what we would call its performative aspect:

The connection of mimetism and such circles [markings on the wings of the Caligo prometheus butterfly] cannot be due to chance. There is a link between the two phenomena that we have to discern. I perceive it in the display mechanism of these fascinating circles. It is not enough for them to exist, they have to appear. Initially invisible, they suddenly burst into view [when the butterfly opens its wings]. Camouflage merges [the insect] with its environment and prevents it from being seen. But then suddenly, where there seemed to be nothing, two enormous circles emerge, vivdly coloured, improbable, whose fixedness fascinates…. The insect operates in the manner of a fold-out mask: it substitutes one appearance for another, which frightens. Or better: instead of nothingness, there is suddenly the face of terror.27

Here Caillois reaches a position that is very close to Nabokov’s in its attention to the theatrical nature of camouflage, but as far as I know, Caillois was not aware of Nabokov’s work.28 In any case, neither writer’s reflections on camouflage were taken up by biologists at the time of their publication, and both remain controversial among historians of evolution theory.29

After genetic accounts of camouflage were developed, the topic returned to the center of the life sciences in the 1990s. The shift occurred primarily because research into the physical mechanisms that produce camouflage features in animals and the perception of camouflage by predators had taken off.30 Another contributing factor was the resumption of discussions on the respective roles of nature and culture in the development of human and nonhuman animals. These conversations picked up nearly a century after the failed attempts, about 1900, to map the development of the human species onto the adaptive behavior of individual animals and humans—that is, to map phylogeny onto ontogeny. Those earlier efforts had been particularly popular in Germany, where Nietzsche claimed that mimicry in humans is one of the constituents or crucial instruments of the Wille zur Macht (will to power).31 In an argument that announces many of the themes of present-day discussions about mimicry, he rejected the survival of the species as mimicry’s main driver, arguing instead that mimicry is the main realization of the will to power, especially in the weak, who must be deceitful to survive. Nietzsche added another consideration: that of the aesthetic luxuriance and variety of mimicry in nature. Pigments, he contended, are produced in nature to please and seduce. They exert yet another variety of power, since the resulting seduction robs its object of free will and attention and acts on its emotions. Thus, pleasure and attraction are the origins of both art and lies.

There is still another implication: for strategies of pleasing and seduction to succeed in protecting potential prey, the prey needs to understand the mind and desires of the predator. The primal situation of ornamental pigmentation, created for survival, seduction, and aesthetic pleasure, is therefore also the origin of empathy, of understanding other minds, and of psychology. This is stated clearly in Nietzsche’s Morgenröthe (1881), one of the most explicit and sustained projections of animal mimicry onto human behavior:

Animals and morality.—The practices demanded in polite society: careful avoidance of … the presumptuous, the suppression of one’s virtues as well as one’s strongest inclinations … all this is to be found as a social morality in a crude form everywhere, even in the depths of the animal world—and only at this depth do we see the purpose of all these amiable precautions: one wishes to elude one’s pursuers and be favoured in the pursuit of one’s prey. For that reason the animals learn to master themselves and alter their form, so that many, for example, adapt their colouring to the colouring of their surroundings … or assume the forms and colours of another animal or of sand, leaves, lichen, fungus (what English researchers designate [as] “mimicry”)…. All the subtle ways we have of appearing fortunate, grateful, powerful, enamoured have their easily discoverable parallels in the animal world.32

In the 1990s and 2000s the old nature/nurture debate concerning camouflage was revived because the impact of behavior on genetic modification had become increasingly apparent, as had the transmission of knowledge and skills over generations within a species. 33 Finally, the revival of animal ethology by Frans de Waal and other primate specialists showed again, from a different perspective, that camouflage and mimicry are not determined solely by the genetic pool but that such strategies are culturally constituted practices, among animals as among humans, that draw on empathy, as Nietzsche had argued.34

2. Camouflage and mimicry in human culture and behavior

2.1. Camouflage in hunting

Long before their codification in evolution theory, camouflage and mimicry were part of human culture. Among the oldest-surviving human artifacts are depictions of humans masquerading as animals: a cave painting from South Africa from ca. 30,000 BCE shows a huntsman wearing an animal mask and tail (fig. 9). During building works in Berlin in 1953, a giant mask made from the skull and antlers of a deer was found. Created between 8770 and 8750 BCE (fig. 10), the object belongs to a group of early Mesolithic antler masks or caps found in Germany as well as in Star Carr, near Scarborough, England. The careful cutting of the skull, the removal of half of the antlers, and the holes drilled through the skull so that it could be fastened to the wearer’s head show that this prey was adapted to become a mask.35The oldest-surviving written description of a masquerade in which humans take on the physical characteristics of an animal to avoid detection is probably Homer’s account of Odysseus’s escape from Polyphemus. The Greek hero’s subterfuge—he passes his comrades off as the blinded giant’s sheep—is depicted, for instance, in Jacob Jordaens’s painting of circa 1635, now in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow (fig. 11).36

The use of camouflage among animals and humans was well documented in antiquity. Aristotle described the octopus’s changes in color to adapt to changes in its environment, and Philostratus recorded pirates’ use of protective coloring for their ships.37 The treatise on fishing by Oppianus of Cyzicos, written about 180 CE, and the epic poem on hunting written by Oppianus of Apameia after 198 CE, discuss camouflage elements in the traps, nets, and other devices used to catch prey.38 As Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant have pointed out in their study of cunning in Greek culture, camouflage was employed by both animals and humans; both take on the role of the hunter and the hunted. Marine animals in particular were known to excel in the use of adaptive coloration: “By means of their technè octopuses disappear into the rock to which they attach themselves.”39 Dissimulation is practiced equally by the hunter and the hunted: “silent and invisible, hunters and fishermen alike must make themselves into prey.”40 The print cycle Venationes Ferarum, Avium, Piscium (Chasing Wild Animals, Birds and Fish), engraved by Philips Galle in 1578 and based on designs by Jan van der Straet (known as Stradanus) for the Medici Villa at Poggio a Caiano, shows the use of so-called Attrappe-Kuhen (catcher cows) that served as decoys for deer and protective covering for the hunters (fig. 12). Contemporary captions to two of these prints point to major elements in subsequent discussions of camouflage as a cultural technique: its fictional character and its being a kind of dress or costume. One of the captions states that hunters protected by fictional cows kill the frightened deer; the other explains that the huntsman proceeds dressed as a cow.41

Dissimulation as the wider cultural concept for understanding animal and human behavior returns in emblem books. Published in 1664, the emblem book of Jacobus Bornitius contains an image that had appeared twenty-seven years earlier, in Jacob Cats’s Proteus ofte Minnebeelden verandert in Sinnebeelden, of 1627. It shows a bird-catcher keeping an eye on his traps from behind the dappled patterns made by the leaves of the tree in which he’s hiding. The device carries this warning: “Look carefully whom you trust: such is the dissimulation of the world!/If somebody says something, he denies it: if he denies it, he says it of himself.”42

Dissimulation was often identified as a defining feature of civilized life in the early modern period: it is a frequent topic in manuals for courtiers, such as Castiglione’s; it was captured in the title of Torquato Accetto’s treatise on honest dissimulation; and it is often connected to visual depictions of princely behavior, such as those in Rubens’s Medici cycle.43Accetto defines dissimulation as the concealment or disguise of something, as opposed to simulation, which is the pretence of what is not, in affectation, fabrication, or counterfeiting.44 Thus defined, dissimulation unites aspects of crypsis (avoiding detection) and masquerade (preventing recognition). Indeed, sometimes a connection is made between human dissimulation and animal camouflage: Baltasar Gracián advises the courtier that “the most practical sort of knowledge lies in dissimulation…. Oppose lynxes of discourse with inky cuttlefish of interiority. Let no one discover your inclinations, no one foresee them, either to contradict or to flatter them.”45 Gracián’s counsel suggests that dissimulation in humans often connected to their indulging in their irrational, animal nature.47

Animal features figure prominently in one of the most detailed studies of human social camouflage and mimicry, the Mémoires of the duc de Saint-Simon (1675–1755). Published in the nineteenth century following the royal sequestration of the manuscript after the author’s death, the work gives a full and surpassingly vivid account of the last decade of the rule of Louis XIV and the Regency. It also stands out for its depiction of court life as a menagerie in which aristocrats strive to adapt their behavior to that of the royal family and new arrivals or social climbers attempt to camouflage traces of their lowly origins. This rendering of court life in terms of animal behavior is underpinned by Saint-Simon’s use of animal traits and metaphors to characterize the subjects of the written portraits that punctuate his narrative.

Thus, the courtier Henri Pussort has the face of an angry cat; the Villars couple are two-legged rats who flee the court of the dying king just as rats flee houses on the brink of collapse; Jeanne de Mouchy-Montcraval is a woodcock; the prince de Carignan, a circus animal; the marquis de Feuquières, a furious dog; the Abbé de Vaubrun, a vile and dangerous slug; the comte de Pontchartrain, a poisonous spider; the duc du Maine, one of the king’s bastard sons, a rattlesnake. The duc de Noailles is the perfect imitation of the snake who corrupted Paradise; the Prince de Condé believes himself to be a dog, whereas the servants of the duc de Vendôme behave like a pack of hunting dogs. The duchesse de Gesvre resembles a crane in her overall appearance and gait.48 Incidentally, cranes featured prominently in the zoo at Versailles and in representations of its animals in the sumptuous cycle of tapestries commemorating royal residences and the months of the year. Exotic animals in the foregrounds of those woven scenes often mimicked the behavior of courtiers, their gestures and bearing (fig. 13).

Saint-Simon’s character sketch of the duc de Noailles merits close scrutiny because it shows clearly the author’s use of animal hypotyposis and metonymy to analyze camouflage behavior. “The serpent who tempted Eve, who overturned Adam through her, and who ruined the human species, is the original of which the duc de Noailles is the most exact, the most faithful, the most perfect copy…. A life spent in darkness, closeted, enemy of light, preoccupied by his ambitions … depth without substance…. Language of the courtier, jargon of women, convivial, without taste if necessary, dressed instantly according to the tastes of anybody he is with.”49

These few short sentences present a compelling portrait of social mimicry. The dissimulation of the duc de Noailles is not the behavior expected of a courtier who has read Castiglione on the ideal comportment of someone of his rank or Torquato Accetto’s essay on honest dissimulation. It is instead an integral part of what Saint-Simon considers to be the duke’s profoundly bestial nature. The effect that Saint-Simon’s description of the duke has on the reader, like the cumulative effect of all the other zoomorphisms in the portraits of the inhabitants of Versailles, creates profound uncertainty about the ontological status of the animal in the Mémoires as well as at the court. Is the author’s use of animal traits to evoke or, rather, figure the character of the courtiers simply a stylistic strategy? If that is so, why do these identifications work so well? Are these courtiers in fact poorly disguised animals and Saint-Simon is the one who rips off their human masks? Or are they humans who fail to master the animal parts of their nature? An affirmative response to this last question is supported by a passage in which Saint-Simon notes that when the duc de Beauvillier, bereft of his best friend, masters his grief, he completes the destruction of his inner animal nature.50

Saint-Simon was not unique in playing on readers’ uneasy awareness of the fragile border between animal and human nature. La Fontaine’s Fables exercised their hold on the popular imagination in part because of their ontological oscillations: it is never quite clear whether they portray humans disguised as animals or animals disguised as humans. Another major ingredient of this new figuration of animality was contributed by Charles Le Brun (1609–1690), first painter to Louis XIV. Le Brun’s studies of animal and human physiognomy culminated in renderings of unsettling faces that combine animal and human features and thus transcend the barriers between species (fig. 14).51When the studies were displayed at the Louvre in 1794, crowds flocked to the exhibition, making it the museum’s most popular attraction. The journalist and urbanist Sébastien Mercier gave a suggestive account of viewers’ reactions, reporting that they scrutinized Le Brun’s drawings and then started to search the faces of people around them for likenesses to animal faces. At the end of their visits, the spectators all slunk away to cast furtive glances in the mirrors hanging near the exit, where they checked to see whether they themselves looked like eagles or chickens, camels or lions, apes or swine. “It is an instinct,” Mercier wrote.52

All the approximations of animal and human behavior and appearance cited above—particularly Saint-Simon’s animal figurations of human camouflage and mimicry—are instances of cultural practices or techniques in the sense outlined in the introduction to this article. They arise in a context of newly emerging social and scientific cultures; they are concerned with the construction and presentation of social identities; and they lend themselves to reflection and thematization. The anecdote by Mercier is particularly telling, as it presents both the first-order visual questioning of the relation between the animal and the human by Le Brun and the second-order thematization of that questioning in the reactions of those who attended the exhibition of his work.

2.3. Masking and the emergence of human culture

In the 1860s, at the time of Darwin’s and Wallace’s first theorizations of camouflage as a means of the survival of species, the architect and architectural theorist Gottfried Semper (1803–1879) developed a theory of the emergence of human material culture in which masking plays a central role. Semper was well aware of evolution theory but felt its analysis of the development of species was too general and on too large a timescale to be applied profitably to human culture. Yet what he said about dressing and masking as the defining characteristics of art and about their theatrical essence comes strikingly close to what Wallace said about the theatrical aspect of animal camouflage—that it can make animals appear as actors or masqueraders.

For Semper, all cultures originate in what he posited as the four primitive crafts: weaving, carpentry, masonry, and metalwork. Human societies emerge when a tribe gathers around a fire to tell stories about ancestors and marks off the space with woven grass, fiber, and, subsequently, textile. Thus, a space is created using a partition, pen, or fence made of plaited or interwoven sticks and branches. In a revolutionary move, Semper argues that the origin and essence of architecture are not construction but the visible representation of enclosed space. Architecture is thus intimately linked to weaving or textile, one of the four primitive crafts found all over the world and that form the cradle of human art and industry: “The beginning of building coincides with the beginning of textiles.”53 Inspired by the re-creation of a Trinidadian bamboo hut that he had seen in London at the Great Exhibition of 1851, Semper breaks with the classical tradition of considering the petite cabane rustique —that is, a building and its construction—as the origin of architecture. Instead, in a fundamental rethinking of an artistic tradition in anthropological terms, he located architecture’s origins in the craft of weaving, which made the action of space creation possible by providing woven curtains, carpets, and tents.54

According to Semper, the shift from ephemeral textile constructions to enduring stone structures was impelled by the human drive to create lasting, monumental records of important political and religious acts, situations, and rituals. With the change came dressing and masking: marble slabs, stucco, and polychromy mask and dress the interior structure of buildings. Architecture, Semper maintained, is not an art of construction but of masquerade and disguise, as are most human arts, including the theater. He famously observed that the torchlit masquerade of Carnival is the best atmosphere in which to enjoy art.55

Semper elaborated this hypothetical etiology into an anthropological theory that identifies the innate human urge to act and to mask reality as the origin of all art. (The anthropologist Gustav Klemm, Semper’s contempory, called this urge Darstellungstrieb —the instinctual urge to represent.56) He claimed, in other words, that the material origins of building can be traced to the craft of weaving but that the transformation of building into an art form was sparked by the human instinct to disguise, play, and represent—and thereby to appropriate and survive.57An early Chinese vase now in the Museum Rietberg in Zürich and unfortunately not known to Semper presents a good example of the human urge to mask and disguise. Its textured surface bears the imprint of a woven fabric that was pressed against the vessel’s surface to leave a decorative pattern (fig. 15).

In Semper’s view, the production of masks to be worn on the face, head, or entire body was preceded by the practice of tattooing, which is closely related to cannibalism as a founding rite of human societies. Created by deliberate human action performed directly on the body, tattooing occupies an intriguing intermediate position between the external artifact of the mask and the bodily metamorphosis effected by animal camouflage. Semper argued that polychromy is an externalization of tattooing and that it constituted the first manifestation of the principle of dressing and masking, which for him characterizes all art.

Semper’s concept of masking is closer to masquerade, designed to avoid recognition, than to crypsis, employed to avoid detection. Walls dressed in stucco, marble, or tiles mask the original craft and materials—the masonry or carpentry—used to construct them. The anthropological driver of this transformation of craft into art goes back to humans’ early use of animal masks created through a gesture of appropriation. As I have written elsewhere, it could be argued by extension that animal camouflage and human image-making meet in the mask.58 The mask is a man-made artifact used by humans to hide their real appearance, look like another living being, frighten, terrify, or pass unnoticed—in short, to perform some of the same functions as camouflage, but with different mechanisms. In his magnum opus, Der Stil (1860–63), Semper connected the custom shared by early societies across the world of wearing animal skins and masks to chase away enemies and terrify believers into submission:

Thus even today the Prairie Indians hide their heads behind frightful animal masks during their savage war dances; masks taken from bisons or bears. One finds a similar mask ornamentation among the savages of the South Sea Islands. Such horrible animal masks appear among Egyptian priests in a more refined design as the hieratic head ornament of the priest who represents the god. Thus the animal mask became the early symbol for disguise, hiding, the secret, and the terrifying. Often nothing remained of this except the particularly characteristic features of the animal, as in the use of bull horns to ornament the Mitra of Assyrian rulers…. The terrifying Gorgon of Pallas Athena is a mask. It was long a most significant symbol in life as in the arts before the dramatic arts appropriated it; and here as well we see the apparently most refined product of antique art grafted on the earliest origins of nature. 59

In the next stages of the development of human art, monuments are erected to commemorate the religious, political, or cultural founding moments of a society. Semper describes this progression in what we would now call material culture as a process of Stoffwechsel (metamorphosis, or metabolism), in which motifs associated with the four primitive crafts migrate from one medium to another across time and space. His major example is weaving, which in many respects he considered to be the foundational human craft. It originated in Egypt, developing into fabrics, curtains, and tapestries used to cover walls. These began to be represented on painted tiles in Mesopotamia and subsequently migrated across time, place, and genres into ephemeral hangings used in triumphal processions and ceremonies. This process of Stoffwechsel reached a first culmination in stone representations of tapestries used in ephemeral triumphs that were carved on Roman triumphal arches.

Historians of the decorative arts such as Alois Riegl (1858–1905) demonstrated that many of Semper’s hypotheses about the historical details of cultural development were incorrect. Nevertheless, Semper’s theory of the emergence of human culture in the transition from primitive crafts to artistic practices such as tapestry-making and architecture is, in my view, one of the best and most fully documented studies of the advent of what we would now call a cultural technique. Weaving existed before it was conceptualized, it developed into a codified practice inextricably linked to its medium, and it is clearly capable of thematization. Semper’s concept of Stoffwechsel elucidates this process of emergence. His theory of dressing and masking and the theatrical nature of the visual arts—theatrical in that they are always meant to be seen—is a particularly telling analysis of how thematization in the visual arts and architecture can work.60 And not least, Semper offers an understanding of camouflage, here in the sense of masquerade, as a human cultural technique that originates in the appropriation of animal heads as masks to be used in the same way animals use facial coloring and expression to hide or to terrify.

Conclusion

Despite the evident and often striking similarities between animal camouflage or mimicry and human image-making, understanding this relation is not easy because of the complexities that appear once those similarities are questioned. These complexities include how to relate the respective evolutionary developments of animal camouflage and human image-making and how to relate the visual and intellectual competences implied by camouflage that enable both animals and humans, as Caillois suggested, to see circles as eyes and in general to see something as something else—the phenomenon known as “seeing in/ seeing as,” or aspectual seeing.61Considering human behavior or image-making in terms of camouflage and mimicry raises complex issues about intentionality and the degree to which such behavior, even though it looks very similar to animal appearance and behavior, is in fact related to it. Before we start to define this relation, a corpus of cases of human camouflage and mimicry needs to be established; and to establish that corpus or catalogue, criteria for inclusion and categories to guide the search for cases have to be defined. Defining human camouflage and mimicry as cultural technique is a first step that offers a way of thinking about the relation between nature and culture. The three contexts outlined here for such human behavior and image-making are pointers that can guide further searches.

Notes

Caroline van Eck is professor of art history at the University of Cambridge and the author of Piranesi’s Candelabra and the Presence of the Past: Excessive Objects and the Emergence of a Style in the Age of Neoclassicism (Oxford University Press, 2023).

I am much indebted to the suggestions of two anonymous readers of this article. I greatly benefited from conversations at seminars of the Cambridge-Ghent Network for Camouflage with Maude Bass-Krueger, Lorenzo Bartalesi, Caroline Humphrey, Stijn Bussels, Philippe Descola, Pascal Griener, Odile Nouvel, and Bram Van Oostveldt. I am even more indebted to Hende Bauer for her deep knowledge and endless patience in answering my questions about evolution theory.