Camouflage is not the exclusive domain of animals. Humans also practice it, in hunting, war and fashion, social behaviour, and the arts. It is not restricted to artefacts; it also occurs in social behaviour, when people disguise their social status, desires, or motives behind appearances they judge to be more acceptable or effective. The shared domain of animal and human camouflage and mimicry raises many psychological, cultural, behavioural, and evolutionary questions about the relations between such animal and human behaviour, but it also offers new ways of thinking about the relations between human and other animals, the evolutionary origins of cognition, image-making, and empathy, and new departures for a dialogue between the humanities and life sciences.

Camouflage and mimicry behaviour among animals and humans has been observed and documented since Homer in the West. It received its scientific codification in the work of Bates, Wallace, and Darwin, where it served as one of the first testing grounds for the theory of survival of species through adaptation to environment. In the run-up to World War I military camouflage was much studied by artists such as Abbott Thayer, who tried to establish its principles.

Yet from the 1920s different views and perspectives began to be developed. Surrealists became very interested in it as a poetics of artistic creation. In the 1960s the novelist and entomologist Vladimir Nabokov and the Surrealist Roger Caillois independently of each other voiced a very similar criticism of evolutionist explanations of camouflage and mimicry. For Nabokov its infinite richness could not be explained by the endless hit or miss and tinkering of survival by adaptation. In Le Mimétisme Animal (1963) Caillois made the similar point that there is an excess of image-making that cannot be explained by adaptation to survive. Instead, Caillois argued, one should consider camouflage and mimicry as one manifestation of an underlying primary competence, the capacity to take something for something else, for instance to see a circle and interpret it as the eye of a dangerous animal.

These intuitions were not followed up at the time of publication, but they are now slowly finding echoes thanks to the advance of research into primary human and animal cognitive capacities. Also, in the past decades research into camouflage and mimicry was renewed because of significant advances in the knowledge of their physiology in animals.

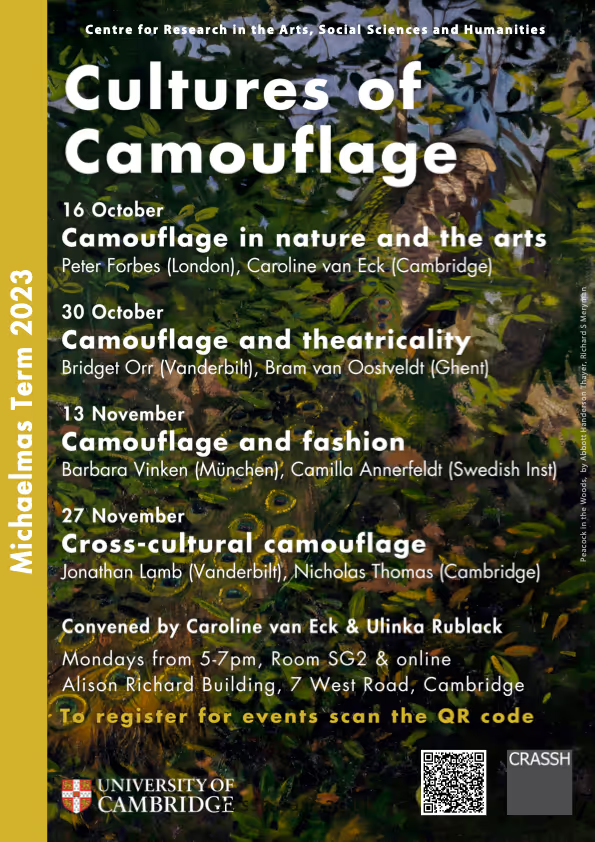

In this network we will look at the various artistic, biological, behavioural and psychological issues raised by thinking about camouflage and mimicry as a domain of behaviour and artefacts or images shared by human and non-human animals. The network meets twice a month, on Mondays, from 5 to 7 pm, in hybrid sessions, at CRASSH. In Michaelmas the speakers are:

16 October 2023: Camouflage in nature and the arts

- Prof. Caroline van Eck: Camouflage Research: A State of the Art

- Dr. Peter Forbes (City University London): Drawing the World. The Art and Science of Mimicry

Animals and plants are patterned to have designs on other animals and plants: to reproduce, to capture or evade capture. The patterns they exhibit in this empire of signs cross the plant/animal divide, are often judged beautiful by humans, and are used as source material for their own pattern making. The talk draws widely on artists and scientists who have drawn out and exploited these connections, and delves beneath the surface to explain some of nature’s processes that underlie these phenomena.

30 October2023: Camouflage and Theatricality

- Prof. Bridget Orr (Vanderbilt): Camouflage Labs: mimicry, disguise and presence in 18th century theatre

Theatre is pre-eminently a site of phenomena cognate with ‘camouflage’, namely mimicry and disguise, as anti-theatricalists have complained for millennia. In the eighteenth-century, three issues seem particularly salient in this context. As systems of status differentiation via costume and social performance were increasingly undermined by commerce, the anxieties and potentials of social mimicry proliferated in play scripts and performances. New theatrical modes such as Harlequinades and pantomime exploited a novel corporeal dramaturgy’s capacity to provide uncensored satire through visual performances whose meanings could be inferred without verifiable texts. And in acting theory, a lengthy contest between ‘externalists’ who believed actors could perform universal signs of passion without genuinely feeling the emotions they represented, and ‘internalists’ who believed actors needed to embody feelings authentically, put affective mimicry at the centre of theatre’s claim to moral and social value.

- Prof. Bram Van Oostveldt (Ghent): Mimicry andCamouflage in Eighteenth-Century Acting Theories

Darwin, Bates and Wallace often use theatrical metaphors to describe mimicry and camouflage in the animal world. Wallace compares Leptalis-butterflies to actors and masqueraders, while Darwin refers to theatrical strategies to understand mimicry and camouflage in the animal world.In their turn, 19th-and early 20th-century writings on acting, such as William Archer’s Masks orFaces? A study in the Psychology of Acting (1880), R.J Broadbent’s History of Pantomime (1901) or Arthur Bleakley’s The Art of Mimicry (1911)compare the art of acting to strategies of camouflage and mimicry in the animal world. Whereas these comparisons between theatre and camouflage and mimicry in this period are merely used as metaphors, eighteenth-century theoretical reflections on acting can give us some more profound ideas about this connection. Although the words camouflage and mimicry are not used, acting is considered to be a chameleon-like activity that tries to understand the relation between character performer and spectator in terms of hiding and deceit. In this paper, I will focus on French and English 18th-century acting manuals (Rémond de Saint-Albine, François Riccobini, Diderot and JohnHill) to explore these connections in terms of a methodology for acting, but also focus on how they raised important questions about social behavior.

13 November 2023:

- Prof. Barbara Vinken (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München): Camouflage and Fashion

- Dr. Camilla Annerfeldt (Swedish Institutefor Classical Studies Rome): A Paradise for Impostors?Clothing and Identity in Early Modern Rome

In early modern Rome, social identity was regarded as much more important than the individual, and clothing has therefore often been seen as a manifestation of the social order. The social hierarchy was reflected in hierarchies of appearance, in which clothes constructed the social body. Accordingly, what one wore should mark prescribed identities – of gender, age, marital status, rank, and nationality – as well as signal one’s profession and political allegiances.

Yet, the clothes one wore could also create a desired identity. Clothes functioned as an alternative currency. Garments were repaired and remade, circulated as perquisites, wages, gifts, or bequests, or were pawned, or sold on the second-hand market if the necessity arose. This constant circulation of clothes could thus create confusion within the hierarchies of appearance; by acquiring clothes otherwise out of reach of one’s socio-economic range, the wearers were enabled to ‘appear what they would be’ rather than as they were.

In this paper, I will describe how clothing was used by the members of Rome’s different socio-economic classes as a token to accentuate – or mislead – their social standing. Moreover, as this paper will explore in greater depth, it could be argued that in terms of the ‘rigid’ rules regarding early modern dress, Rome offered a kind of middle ground – neither too strict nor too lenient. There can be no doubt that Rome was extremely hierarchical, but the notion –well-established in dress historical research – that one was supposed to dress solely according to one’s social station does not always seem to have been applicable to Roman society. By highlighting some of the ways in which Rome differed from other Italian cities both politically and socially, this paper seeks to elucidate if early modern Rome could be regarded as a paradise for impostors.

27 November 2023: Cross-Cultural Camouflage

- Prof. Jonathan Lamb (Vanderbilt University): Cross-Cultural Camouflage) with Prof. Nicholas Thomas (Museum ofArchaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge) as discussant:

There are three distinct categories of camouflage that herd under a generalization suitable to them all, namely you imagine (or you know) that you are visible to another pair of eyes, and you wish to modify that situation. The modifications are basically three:

(a) you wish to be even more visible than you are already.

(b) you wish to be invisible.

(c) you wish to be seen differently from how you presently appear.

The first modification is mostly aggressive, like the markings on a wasp or a sea-snake, or painting the nose of a fighter-plane to look like a shark with its mouthopen. The second is more or less the opposite, a discreet removal from the eye you imagine has seen you, but it is worth noting that this relies upon a feat of projection on the part of the viewee, whose camouflage will only be as successful as the projection. The third is a more extensive category of wishing, responsible for the immense success of fashion industries in selling cosmetics, clothing, hairstyles, music, cars and holidays. Here the projection used by category (b) is calculated for just the right equipment, in just the right place and at just the right time to appear neither extraordinary nor under par, but precisely comme Il faut. It is an artificial species of sympathy that neither wishes to obtrude nor be ignored.

I aim to talk about two examples of camouflage, namely blushing and tattooing. Insofar as it is a spontaneous action of the body, unwilled, blushing fits none of these categories, but it has something in common with (b) in that it is a reaction that changes one’s colour. Tattooing fits (a) in some circumstances and (c) in others, for in one the contexts I shall be examining it is fully intended to astonish and possibly confuse the viewer, whereas in a case of blushing it is usually the person viewed who is abashed, angry or trying to evade the consequences of being seen.

My examples will start with a marginal illustration to Hogarth’s picture The Country Dance, which he used to illustrate what he had to say about blushing in his book of aesthetics, TheAnalysis of Beauty. I want to compare it with two examples of Maori tattooing that came back from the South Seas in Cook’s Endeavour. The first is a standard example of what is called moko, and is still used today. The second is a much more elusive pattern from Cape Brett, called puhoro, and is coming back into fashion as an arm, leg and thigh ornament, but when Cook and his talented artist Sidney Parkinson saw it, was being used as a facial tattoo, but very quickly disappeared in that form after contact with Europeans. I want to ask what these three images have in common, how they function as camouflage, paying particular attention to the lines of hatching in each of them, and what kind of action and motion they express.

Please go to https://www.crassh.cam.ac.uk/events/39975/ to register.

Conveners: Caroline van Eck (Department of Art History) and Ulinka Rublack (Faculty of History).